News

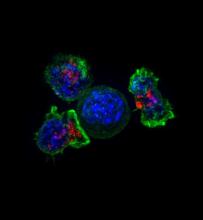

Molecular Zip Code Draws Killer T Cells to Brain Tumors

UCSF scientists have developed a “molecular GPS” to guide immune cells into the brain and kill tumors without harming healthy tissue. It is the first living cell therapy that can navigate through the body to a specific organ, addressing what has been a major limitation of CAR-T cancer therapies

Engineered Immune Cells May Be Able to Tame Inflammation

When the immune system overreacts and starts attacking the body, the only option may be to shut the entire system down and risk developing infections or cancer. But now, scientists at UC San Francisco may have found a more precise way to dial it down. The technology uses engineered T cells that act

47 UCSF Researchers Are Honored for Their High-Impact Science

Nearly 50 UC San Francisco researchers have been named to Clarivate’s list of most influential scientists for 2024. 21 Cancer Center Members: Alan Ashworth, PhD Neal L. Benowitz, MD Atul J. Butte, MD, PhD Adil I. Daud, MD Felix Y. Feng, MD Lawrence Fong, MD Kathleen M. Giacomini, PhD Martin Kampmann

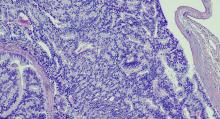

Engineered Receptors Help the Immune System Home in on Cancer

Most cancer treatments – from chemotherapies to engineered immune cells – have a host of side effects, in large part because they affect healthy cells in the body at the same time as targeting tumor cells. For the same reason, designing new cancer drugs can be challenging due to the molecular

Curiosity and the Pursuit of Scientific Discovery: Q&A with Alex Lee, PhD

Alex Lee, PhD, a bioinformatician in the Sweet-Cordero lab, recently received an R50 training grant from the NCI. This salary-based award, which received a perfect score from reviewers, will allow Lee to explore additional research interests and collaborate with other labs in addition to his regular

This AI Tool Helps Neurosurgeons Find Sneaky Cancer Cells

When brain tumors recur, survival rates go down, and patients with the most lethal tumor type often die within a year. That’s because cancerous tissue is left behind after the initial surgery, and it continues to grow, sometimes even faster than the original tumor. Now a new study, led by UC San