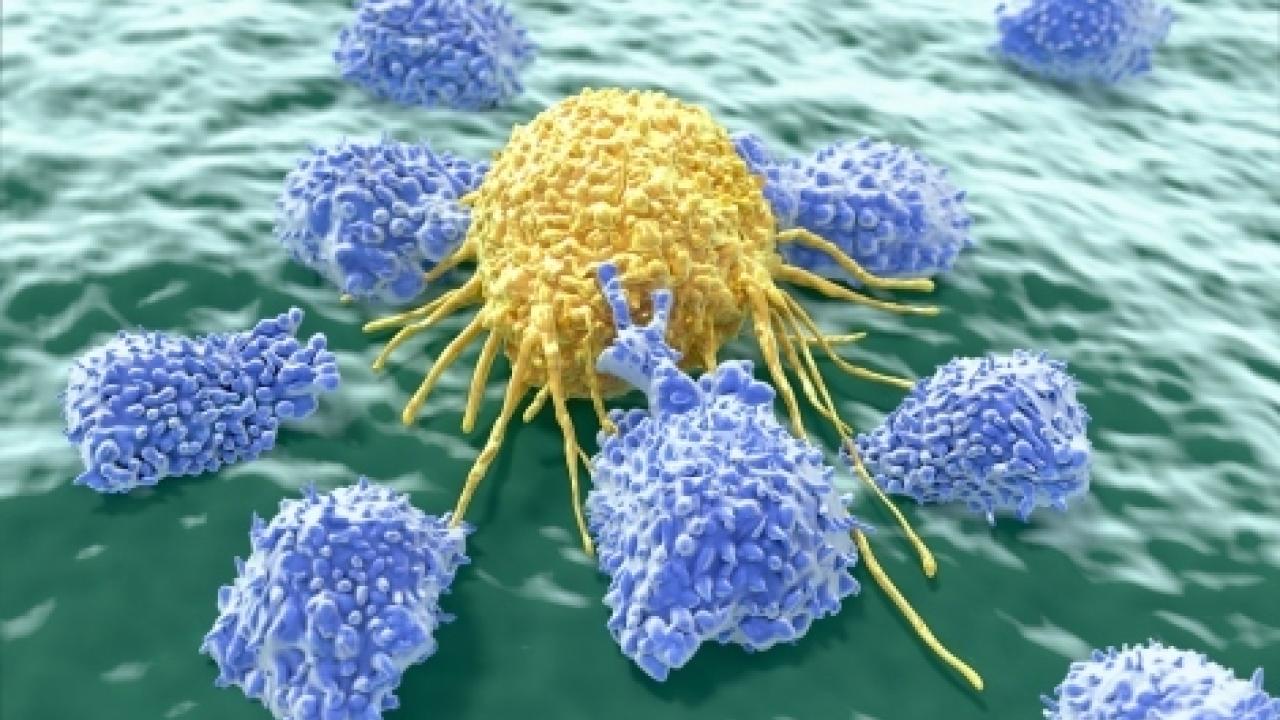

New research led by researchers from UC San Francisco and Stanford University has found that successful cancer immunotherapy appears to depend on whether the treatment can trigger a system-wide immune response, rather than just a local response within the tumor itself. Specifically, data from both mouse models and human patients indicated that successful immunotherapy activates a population of peripheral “memory” immune cells that the researchers speculate are key to immunotherapy’s ability to mount a long-term defense against cancer throughout the body.

The findings — published Jan. 19 in Cell — suggest a new explanation for why immunotherapy, for all its promise, has so far only been effective in a minority of cancer patients, the authors say, and offers leads about how to tweak the approach to bring its benefits to many more people.

“Profiling the immune response across the organism allowed us to see that successful immunotherapy involves widespread activation of the immune system in places far from the tumor itself: in the lymph nodes, the bone marrow, in the blood,” said lead author Matthew Spitzer, PhD, a UCSF Parker fellow and Sandler Faculty Fellow, and a member of UCSF’s Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy. “This suggests that priming the immune system for a more systemic response could significantly broaden the effectiveness of immunotherapy.”

Spitzer conducted much of the research for the new study as a graduate student in the labs of Edgar G. Engleman, MD, and Garry P. Nolan, PhD, of Stanford University, and recently joined UCSF as a faculty fellow to continue his work studying how the immune system coordinates its systemic response against cancer and other threats.

Technique Reveals Whole-Body Response

Immunotherapy has been lauded as a transformative new treatment for cancer: in some patients recruiting the immune system to battle cancer makes tumors melt away and stay away. But so far, most patients simply don’t respond. Some forms of immunotherapy, such as anti-PD1 “checkpoint blockade” therapy, are frequently effective against melanoma, but fail to trigger a successful immune response against most carcinomas, which are the most common forms of cancer.

Most previous studies of immunotherapy response have focused on how treatments recruit immune activity within tumors themselves, but in their new research, Spitzer et al took a larger view of the problem, developing a computational platform — which they call “Scaffold” — that let them intuitively visualize the immune response in detail across a whole organism during successful and unsuccessful immunotherapy treatments.