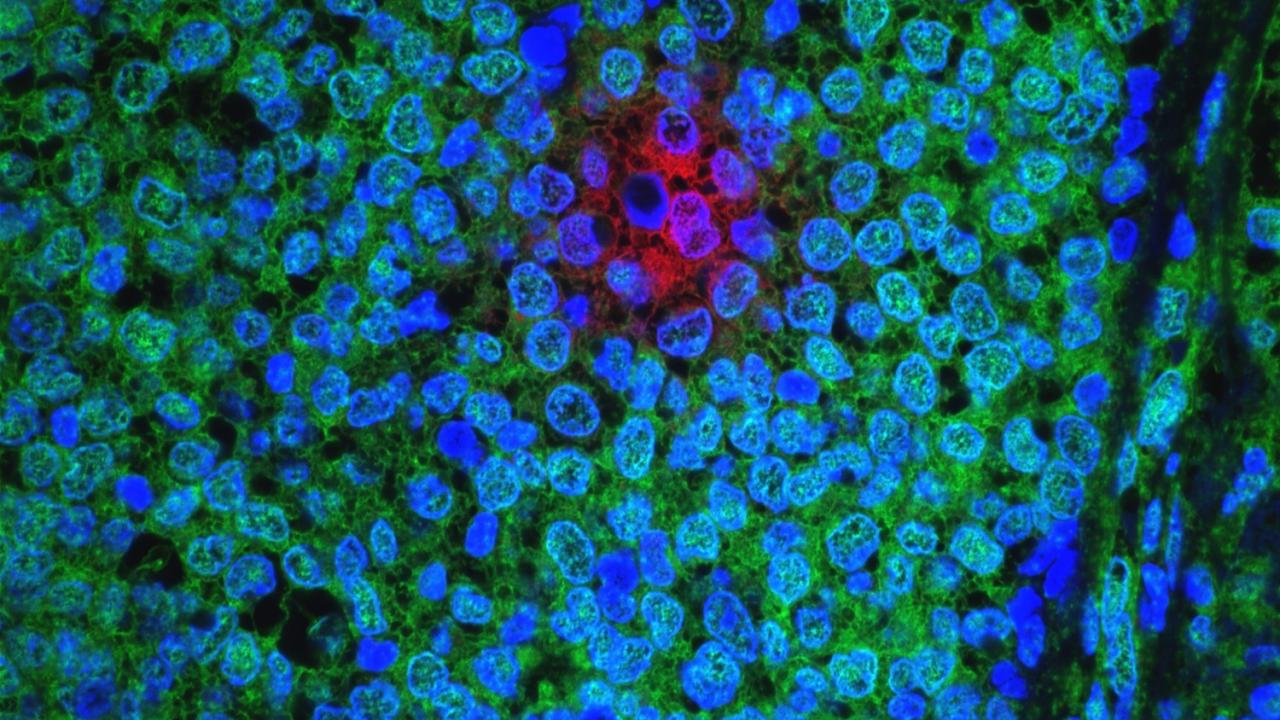

Treatment-Resistant Breast Cancer Cells. Image by Sheheryar Kabraji, Sridhar Ramaswamy. Courtesy of the 2016 NCI Cancer Close Up Collection.

UC San Francisco researchers have discovered a gene vulnerability that could let oncologists wipe out drug-resistant cancers across many different cancer types. The findings, published in Nature on November 1, 2017, suggest a promising new approach to preventing cancer recurrence, if they can be validated in human patients.

Oncologists have typically thought of drug resistance as something that cancers evolve genetically: A few of a patient’s cancer cells either possess or develop new mutations that allow them to survive the effects of therapy — leading to recurrence of new, drug-resistant tumors. However, in 2010, researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center discovered a way cancers might be evading treatment without needing new genetic mutations: Small groups of cancer cells within a tumor, referred to as “persister cells,” exist in a dormant cellular state that allows them to survive drug treatment, then later revive and spawn new cancer growth.

“The precise role of persister cells in the clinic is still unknown,” said Matthew Hangauer, PhD, the UCSF postdoctoral researcher who led the new study. “But many oncologists will tell you informally that non-genetic drug resistance appears to be occurring in patients, and these naturally highly resistant cells are a strong candidate to explain that.”

Recent research, including a 2016 study by Lani Wu, PhD, and Steven Altschuler, PhD, of UCSF’s School of Pharmacy, has suggested that persister cells may act as a residual reservoir of tumor cells during cancer treatment, perhaps surviving multiple rounds of therapy in a dormant state until some cells finally evolve traditional genetic resistance, leading to relapse.

To search for biological weaknesses in persister cells, Hangauer and colleagues used RNA sequencing to look for differences in gene activity between an untreated breast cancer cell line and persister cells from this cell line that survived 9 days of high-dose treatment with the drug lapatinib. They found that persister cells had higher levels of activity in genes typical of mesenchymal cells (the cells that constitute bone, cartilage, muscle, and fat), but less activity in certain genes necessary for cells to withstand oxidative stress.