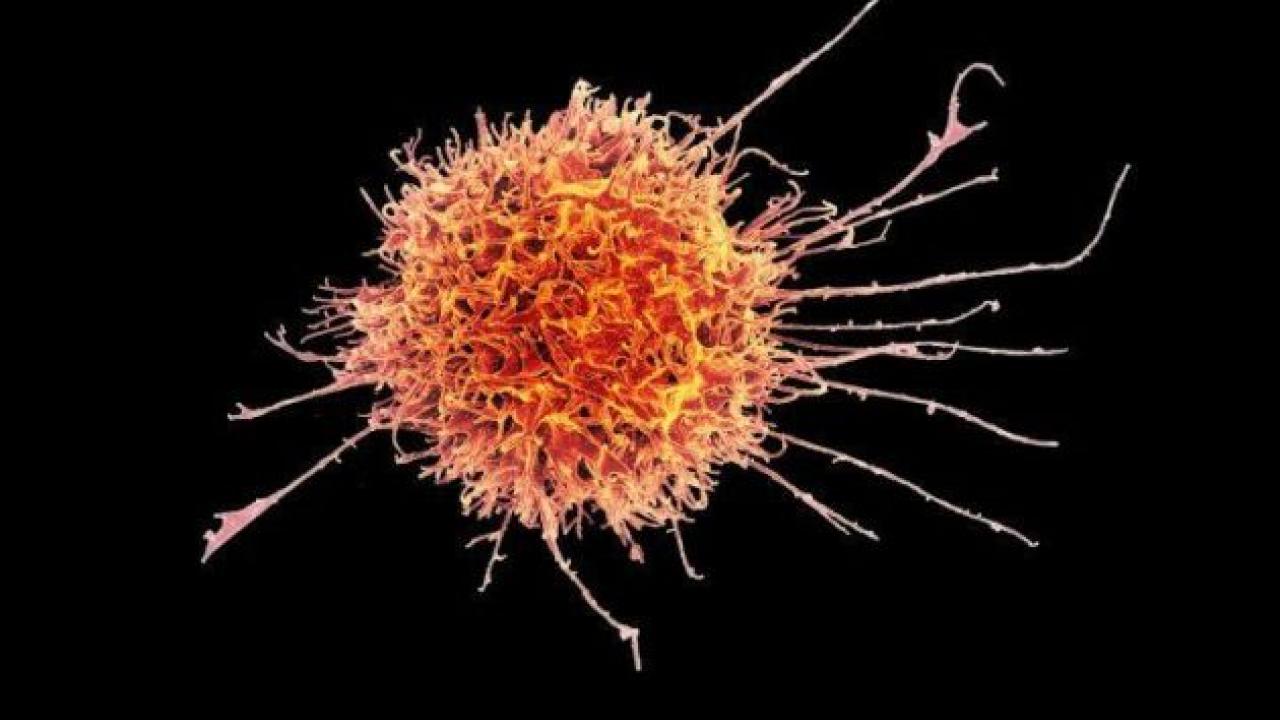

Colorized scanning electron micrograph of a natural killer cell from a human donor. Image by National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

UC San Francisco scientists have discovered a new way to control the immune system’s “natural killer” (NK) cells, a finding with implications for novel cell therapies and tissue implants that can evade immune rejection. The findings could also be used to enhance the ability of cancer immunotherapies to detect and destroy lurking tumors.

The study, published Jan. 8, 2021, in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, addresses a major challenge for the field of regenerative medicine, said lead author Tobias Deuse, MD, the Julien I.E. Hoffman, MD, Endowed Chair in Cardiac Surgery in the UCSF Department of Surgery.

“As a cardiac surgeon, I would love to put myself out of business by being able to implant healthy cardiac cells to repair heart disease,” said Deuse, who is interim chair and director of minimally invasive cardiac surgery in the Division of Adult Cardiothoracic Surgery. “And there are tremendous hopes to one day have the ability to implant insulin-producing cells in patients with diabetes or to inject cancer patients with immune cells engineered to seek and destroy tumors. The major obstacle is how to do this in a way that avoids immediate rejection by the immune system."

Deuse and Sonja Schrepfer, MD, PhD, also a professor in the Department of Surgery’s Transplant and Stem Cell Immunobiology Laboratory, study the immunobiology of stem cells. They are world leaders in a growing scientific subfield working to produce “hypoimmune” lab-grown cells and tissues – capable of evading detection and rejection by the immune system. One of the key methods for doing this is to engineer cells with molecular passcodes that activate immune cell “off switches” called immune checkpoints, which normally help prevent the immune system from attacking the body’s own cells and modulate the intensity of immune responses to avoid excess collateral damage.

Schrepfer and Deuse recently used gene modification tools to engineer hypoimmune stem cells in the lab that are effectively invisible to the immune system. Notably, as well as avoiding the body’s learned or “adaptive” immune responses, these cells could also evade the body’s automatic “innate” immune response against potential pathogens. To achieve this, the researchers adapted a strategy used by cancer cells to keep innate immune cells at bay: They engineered their cells to express significant levels of a protein called CD47, which shuts down certain innate immune cells by avtivating a molecular switch found on these cells, called SIRPα. Their success became part of the founding technology of Sana Biotechnology, Inc, a company co-founded by Schrepfer, who now directs a team developing a platform based on these hypoimmune cells for clinical use.