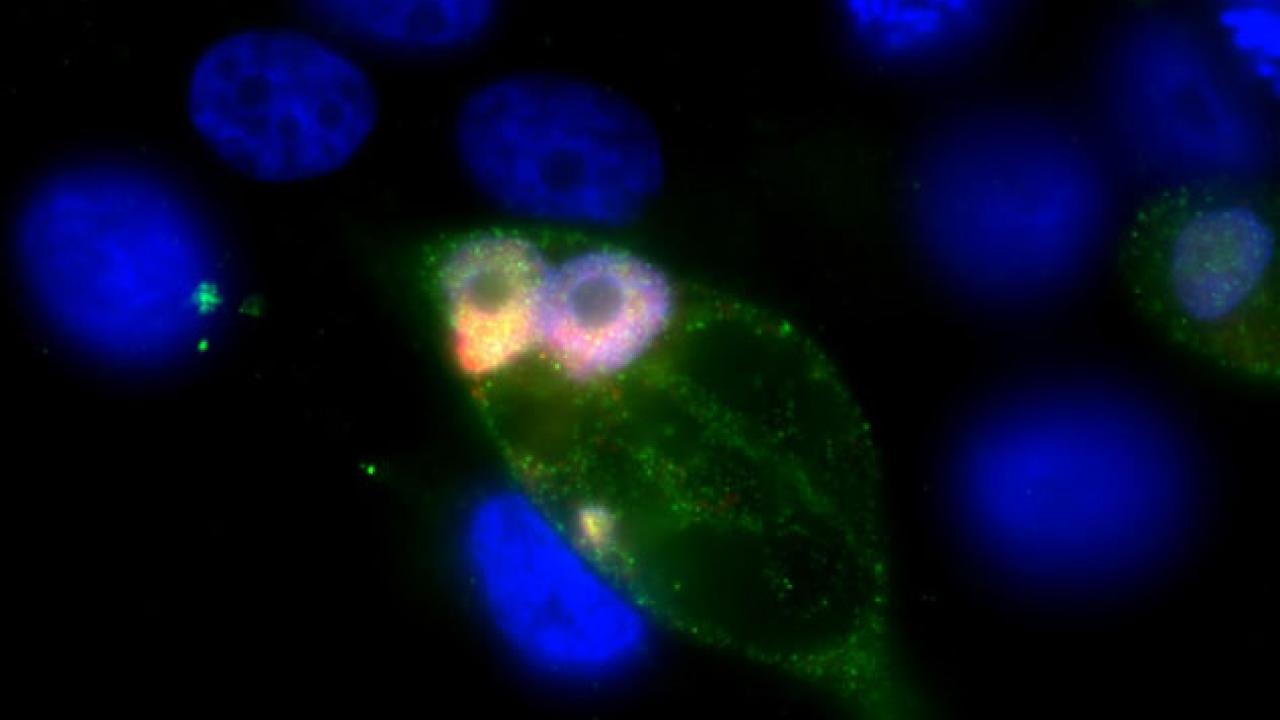

TGF-beta Signaling in Human Breast Cancer Cells. Image courtesy of NCI Center for Cancer Research

Many cancer patients might respond better to treatments with the help of a new prognostic indicator based on a distinctive pattern of gene activity within tumor cells, according to a new study of human cancer data and experiments on human cancer cell lines grown in the lab.

The new research, led by scientists from UC San Francisco and the Catalan Institute of Oncology, in Barcelona, Spain, shows that the newly identified pattern of gene activity is present in many cases of the most common cancers and could be used to predict who is most likely to benefit from “genotoxic” therapies, which include common treatments such as radiation therapy and long-standard chemotherapies.

Mary Helen Barcellos-Hoff, PhD

“The test panel we developed should prove predictive of patient response to genotoxic therapy, and we expect it to be a key for optimizing treatment – either through escalation of the dose in patients with poorer anticipated sensitivity or by combining therapies synergistically that target mechanisms through which tumors resist treatment,” said UCSF’s Mary Helen Barcellos-Hoff, PhD, professor of radiation oncology, who is co-senior author of the new paper with Miquel Àngel Pujana, PhD, of the Catalan Institute.

The work is published in the Feb. 10, 2021, issue of Science Translational Medicine.

Genotoxic treatments, whether chemotherapy or radiation therapy, cause DNA damage, and rapidly dividing or genetically unstable cancer cells are most susceptible to the damage induced by these treatments when they have defects in DNA repair pathways.

Many standard-of-care regimens for different cancers exploit these inherent defects in repair pathways, but patient treatments could be further optimized by knowing which pathway is defective in a given tumor. The new paper offers a method to identify a particular repair pathway that makes tumors most susceptible to genotoxic treatment. Use of the new method could help doctors choose the best therapy by identify which patients may get the greatest benefit.