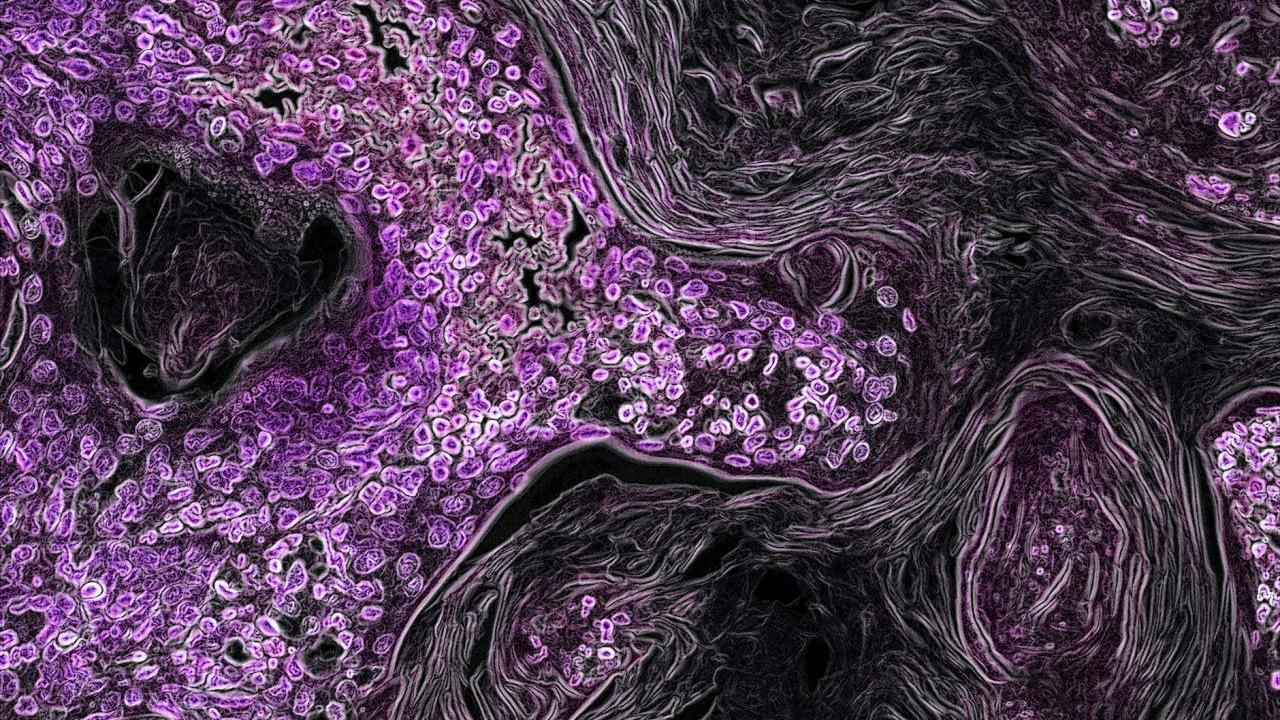

In this image from a genetically engineered mouse model, lung cancer driven by the Kras oncogene shows up in purple. As a key driver in many types of cancer, the Kras gene makes a promising target for new cancer therapies. Image by National Institutes of Health

Over the past two decades, targeted cancer therapies have changed the prognosis for thousands of patients. By targeting the specific genetic mutation behind a patient’s cancer, these therapies have enabled increasing numbers of patients to experience fewer toxic side effects and, often, live free of disease following their treatment.

Twitter Responds to the News

The significance of the news was echoed by the response on Twitter. With more than 500 Retweets and over 2.5K Likes this was the highest performing Tweet from a member of our UCSFCancer community.

It’s time to change this slide! @FDA approval today of #sotorasib. Congrats @JonathanOstrem & Ulf Peters on launching the successful attack with tethering from @realJimWells and scientists at Wellspring! Many steps-great to see the summit reached!! @UCSFCancer @HHMINEWS pic.twitter.com/JSNYXUUspP

— Kevan Shokat (@kevansf) May 28, 2021

But until May 28, 2021, when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved sotorasib for non-small cell lung cancer, there had been no targeted therapy available for people affected by the most common gene-related driver of tumor growth, the protein KRAS.

This long-delayed treatment milestone might not have happened at all without seminal accomplishments by UC San Francisco chemist and Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, Kevan Shokat, PhD, who succeeded in revitalizing a holy-grail-like quest after almost all others had given up.

The Biggest Player in the Deadliest Cancers

Scientists have known since the 1970s – with the Nobel-prize winning discovery of “oncogenes” by UCSF professors J. Michael Bishop, MD, and Harold Varmus, MD – that normal genes within a cell can mutate, causing the cell to turn against the body and develop into life-threatening tumors.

This discovery set off a successful hunt for more cancer-causing mutations – of which more than 100 are now known – as well as efforts to design new cancer therapies specific to those genes. In 1998, the breast cancer drug Herceptin became the first therapy targeted to a specific oncogene, followed by a rising number of oncogene-targeted drugs since then.

Yet KRAS mutations – which are found in about one-quarter of solid tumors and are the leading cause of lung cancer – have managed to elude those attempts.

Oncogenic KRAS was discovered four decades ago and was almost immediately recognized as a significant discovery. But after long and, ultimately, fruitless rounds of drug development, the protein encoded by the oncogene was deemed “undruggable” – a “Death Star” of cancer – and these efforts were abandoned.

KRAS mutations in cancer have remained associated with poor outcomes and failures to respond to other treatments. In lung cancer, which has long been the leading cause of cancer mortality, KRAS mutations drive the growth of about 25,000 new lung cancers each year.

Shokat Finds Hidden KRAS Pocket

The fundamental purpose of the KRAS protein is to carry growth signals from outside the cell to the cell’s nucleus. There, it activates additional biochemical pathways downstream that transmit growth signals within the cell. Cancer-associated mutations cause KRAS to spend most of its time in the “on” position, constantly activating further growth.