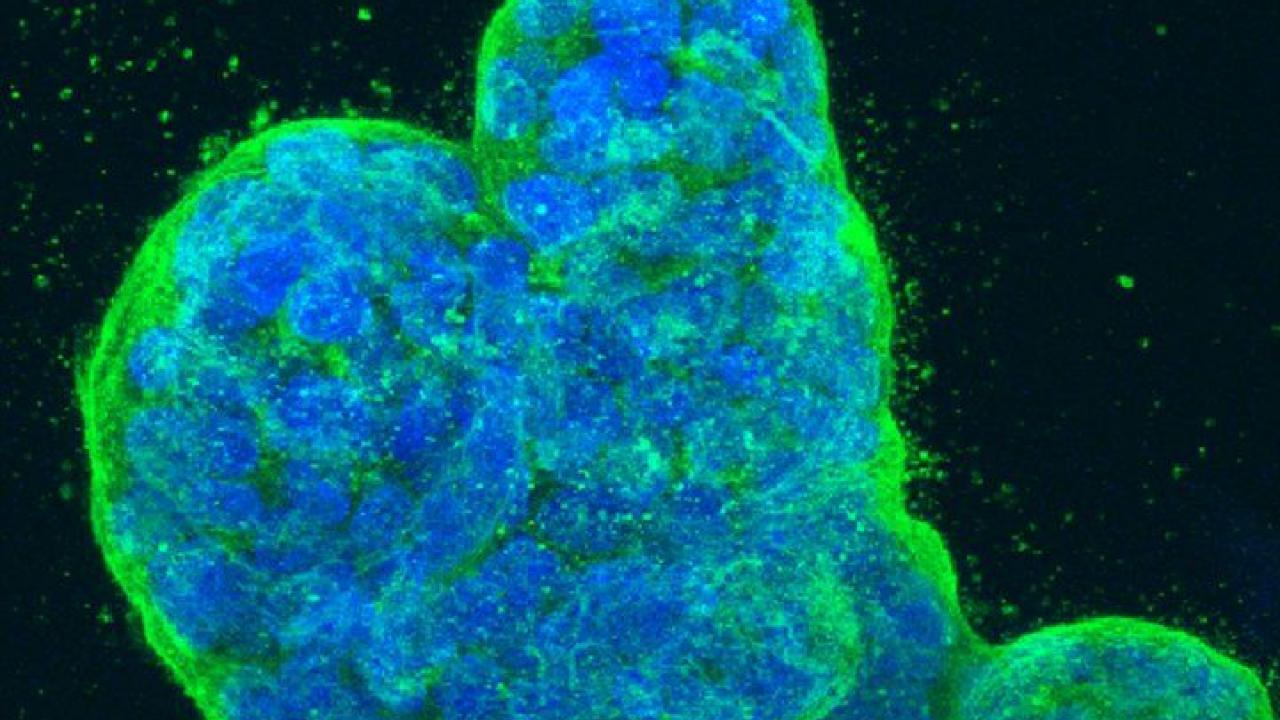

Three-dimensional culture of human breast cancer cells, with DNA stained blue and a protein in the cell surface membrane stained green. Image by NIH

Cancer cells proliferate despite a myriad of stresses – from oxygen deprivation to chemotherapy – that would kill any ordinary cell. Now, researchers at UC San Francisco have gained insight into how they may be doing this through the downstream activity of a powerful estrogen receptor. The discovery offers clues to overcoming resistance to therapies like tamoxifen that are used in many types of breast cancer.

Estrogen receptor α (ERα) drives more than 70 percent of breast cancers. The new research published Sept. 23, 2021, in Cell discovered that in addition to its well-known activity in the nucleus, it can also help malignant cells overcome innate anti-cancer mechanisms and develop resistance to treatment.

In the nucleus, ERα regulates the conversion of DNA to messenger RNA (mRNA), a process known as transcription. Once formed, the mRNA strand travels from the nucleus into the cytoplasm, where it instructs ribosomes to make protein, a process known as translation. To their surprise, the researchers found that ERα plays a role in this process as well by binding to the newly formed mRNA.

"The RNA-centric function of the estrogen receptor has so far been hidden behind its well-established role as a transcription factor, which may have been supporting cancer progression on the sly," said Yichen Xu, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Urology at UCSF and the first author of the study.

A New Role for ERα

Using breast cancer cell lines, the research team saw how ERα tends to bind to RNAs, particularly messenger RNAs (mRNAs) involved in cancer progression. Some of these mRNAs keep cells from committing suicide when they accumulate too many harmful mutations. Others help them proliferate under extremely difficult conditions, such as lack of oxygen or nutrients. Still others help them evade therapeutic interventions.

“Cancer cells are constantly being exposed to stress, and these cells have learned to live with it,” said Davide Ruggero, PhD, the senior author of the study, a professor of Urology and the Helen Diller Family Endowed Chair in Basic Research at UCSF. “Many compounds used to kill cancer induce stress in the cancer, and most of the cancer cells die. But some eventually find a way to bypass the stress induced by the therapy.”