Kole Roybal, associate professor of microbiology and immunology, in his lab at UCSF. Image by Susan Merrell

In recent years, genetically re-engineered immune cells – armed with molecular weaponry to recognize and destroy tumor cells – have changed the landscape of cancer treatment. Now, UC San Francisco researchers have developed a new method for comparing massive numbers of these CAR-T cells, each with slightly different molecular features, to determine which is most effective and long-lasting against cancer.

In their study published Nov. 9, 2022, in Science Translational Medicine, the team used the approach – dubbed “CAR Pooling” – to study CAR-T cells with forty different receptors. The screen, which can be expanded to test hundreds or thousands more receptor combinations in the future, has already revealed new and surprising receptors that make these therapeutic cells more powerful.

“CAR-T cells have been absolutely transformative for a lot of people with blood cancers,” said senior author Kole Roybal, PhD, UC San Francisco associate professor of microbiology and immunology and a member of the Gladstone-UCSF Institute of Genomic Immunology. “This work is a stepping stone toward engineering these cells in even smarter ways so they work better, for longer, and in more cancer types.”

A Transformative Treatment

T cells are a type of white blood cell expressing receptors on their surface that recognize foreign material in the body. When a matching molecule or particle fits into the T cell receptor, the cell launches an immune response to ward off the invader. This kind of response can destroy not only viruses and bacteria, but cancer cells as well.

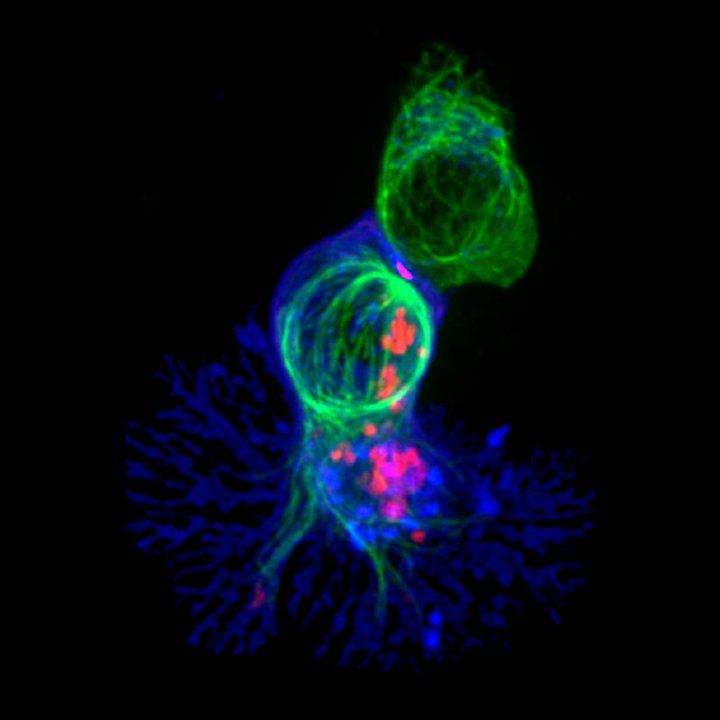

An immunofluorescence image of a killer T cell (blue) engaging a targeted cell. Image by Alex Ritter, Jennifer Lippincott Schwartz and Gillian Griffiths, National Institutes of Health

When a cancer patient is being treated with CAR-T cell therapy, clinicians collect T cells from the patient’s blood or from a healthy donor. Then, they alter these cells in the lab, adding DNA that coaxes the immune cells into producing special, cancer-recognizing chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) on their surface. The modified cells are grown and injected back into the patient. The new CARs help the T cells specifically attack cancer cells. A variety of CAR-T cells have been approved for use in blood cancers, including lymphomas, leukemias and multiple myeloma.