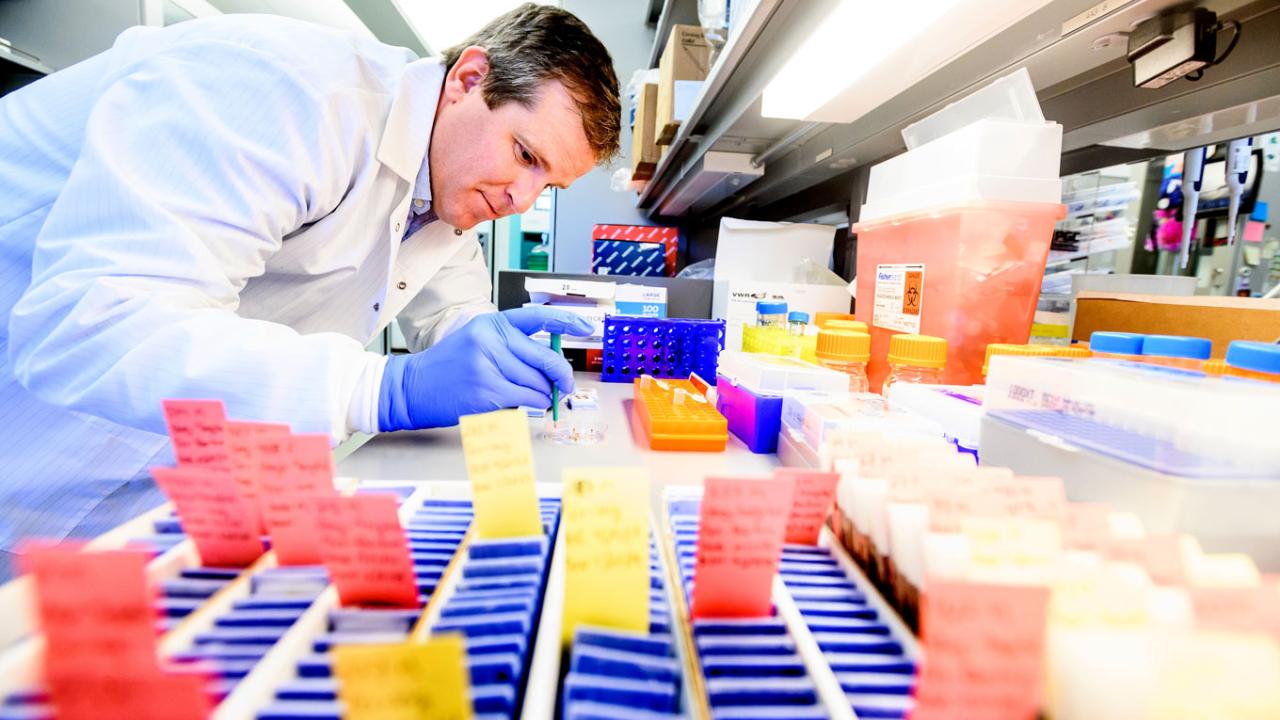

David Solomon, MD, extracts DNA from brain tumor tissue for genomic testing. Image by Noah Berger

Patients diagnosed with a type of brain tumor survived for longer when they were treated aggressively with surgery, radiation and chemotherapy. But far from suggesting that more treatment always leads to better survival, the study by UC San Francisco underscores the critical role of genomic profiling in diagnosing and grading brain tumors.

In the study, UCSF researchers followed 38 patients with a tumor type that was reclassified by the World Health Organization in November 2021, from a grade 2 or 3 glioma, to a “glioblastoma, IDH-wildtype, CNS WHO grade 4,” based on its molecular features. The new more accurate diagnosis comes from genomic profiling in which the DNA alterations that drive tumor growth are identified. The previous diagnosis was determined by traditional microscopic comparisons between cancer cells and normal cells.

All patients underwent genomic sequencing using the UCSF500 Cancer Gene Panel and were offered treatment consistent with a conventional glioblastoma, the deadliest and most common adult brain tumor. The length of their survival was compared with a retrospective cohort of 130 patients with the same tumor type, whose treatment regimens were more conservative, in line with the previous tumor classification.

Brain tumor fragments are being dissected for genomic testing. Image by Noah Berger

The first group of patients survived an average of 24 months, while the second group survived an average of 16 months, the researchers reported in their study, appearing in the online issue of Neuro-Oncology on April 8, 2022, and publishing in the journal’s print version later this year.

“The study shows that genomic profiling resulted in more aggressive patient management that ultimately led to improved clinical outcomes, compared to the biologically matched historical patient cohort,” said senior author, David Solomon, MD, PhD, assistant professor in the UCSF Department of Pathology, investigator at the UCSF Brain Tumor Center, and a principal investigator of the UCSF Glioblastoma Precision Medicine Program.

Early/Evolving Glioblastoma May Have ‘Underlying Biologic Differences’

In studying the MRIs of the first group of patients, the researchers found that 33 of the 38 had imaging features suggestive of a lower-grade glioma, while the remaining five had imaging features suggestive of conventional glioblastoma, such as peripheral enhancement and dead tissue. While both groups were histologically and molecularly indistinguishable, the first set, so-called early/evolving glioblastoma, may have “underlying biologic differences” in the immune micro-environment and an intact blood-brain barrier that may affect treatment efficacy.

The UCSF research was prompted by a landmark 2015 study by the Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network that performed genome-wide analyses on 293 grade 2 and 3 gliomas. The researchers identified a subset of patients, approximately one in five, who lacked an IDH mutation, a molecular biomarker known to be associated with better outcomes. The genomic profile of this subset, which was categorized as IDH-wildtype glioma, mirrored that of the UCSF patients. The patients in this subset were on average 50 years old at diagnosis, about 5 to 10 years older than the patients with IDH-mutant gliomas.