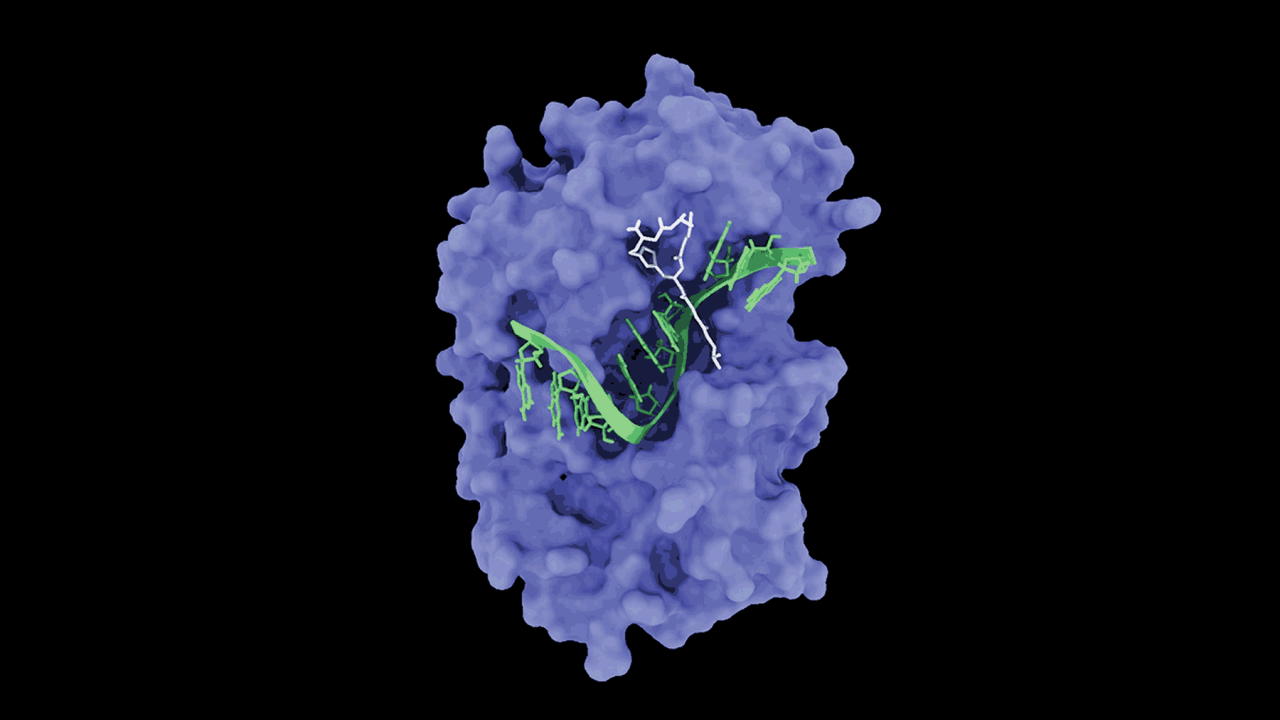

In cancer, the e1F4a enzyme forces cells to make tons of cancerous proteins. A UCSF team found that the breast cancer drug, zotatifin, turns e1F4a, which normally assists in protein production, into a molecular brake. Here, zotatifin (white) sticks to eIF4a (purple) along with an mRNA message (green), preventing the cell from translating the mRNA into a protein. Image by Kuzuoglu-Ozturk et al., Cancer Cell

Swirling inside every cell are millions of microscopic messages called messenger RNAs (mRNAs). The messages are the genetic blueprints for proteins, which determine the behavior and health of the cell.

All mRNAs are packaged to ensure they’re only used at the right place and time – imagine notes sealed in envelopes. But in cancer, enzymes called helicases relentlessly unseal thousands of mRNAs, leading to out-of-control protein production.

Now, UC San Francisco scientists have discovered that a cancer drug called zotatifin that they helped invent turns this process on its head. It disables a helicase called eIF4a, which is plentiful in all sorts of tumors. The drug not only stopped prostate tumors from growing in mice but also made them shrink.

The study, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Prostate Cancer Foundation (PCF), and the UCSF Benioff initiative for prostate cancer research, appears in Cancer Cell on March 20.

“Healthy cells have all sorts of safeguards to prevent cancerous mRNAs from being highly translated,” said Davide Ruggero, PhD, a professor of urology at UCSF, Goldberg-Benioff Endowed Professorship, American Cancer Society Research Professor and co-corresponding author of the paper. “Prostate cancer usurps eIF4A to overcome these safeguards, but we had zotatifin in our back pocket to attack eIF4A. We think it could be a game-changer for treating the disease.”

Targeting the protein factories behind prostate cancer

Zotatifin was developed by the pharmaceutical company eFFECTOR based on the research of Ruggero and Kevan Shokat, PhD, professor of cellular and molecular pharmacology at UCSF. It is currently being tested as a therapy for breast cancer in clinical trials.

Ruggero and his UCSF team suspected that eIF4A might also be misbehaving in prostate cancer, so they screened tumors from 500 UCSF patients with prostate cancer. As the patients’ cancer worsened, their eIF4A levels rose.

The scientists tested zotatifin against prostate tumor biopsies that were transplanted into mice. This type of experiment, called a patient-derived xenograft, is considered a gold standard for showing a drug’s potential to beat cancer in the laboratory.

The prostate tumors, which had been growing relentlessly in patients, shrank in response to zotatifin in the mice.

Ruggero knew that this first result might not be enough to show it worked against prostate cancer, which is one of the most common cancers in men. It is notorious for coming back after diminishing in response to first-line therapies, like hormone therapy and radiation.