Computed tomography (CT) scans may account for 5% of all cancers annually, according to a new study out of UC San Francisco that cautions against overusing and overdosing CTs.

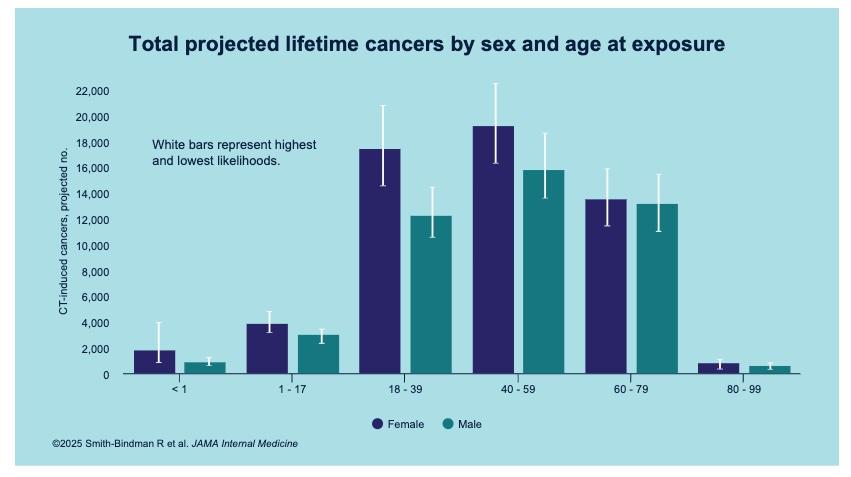

The danger is greatest for infants, followed by children and adolescents. But adults also are at risk, since they are the most likely to get scans. Nearly 103,000 cancers are predicted to result from the 93 million CT, also known as CAT, scans that were performed in 2023 alone. This is 3 to 4 times more than previous assessments, the authors said.

The study, which was funded by the National Institutes of Health, appears April 14 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

“CT can save lives, but its potential harms are often overlooked,” said first author Rebecca Smith-Bindman, MD, a UCSF radiologist and professor of epidemiology and biostatistics and obstetrics, gynecology and reproductive sciences.

“Given the large volume of CT use in the United States, many cancers could occur in the future if current practices don’t change,” said Smith-Bindman, who is also a member of the Philip R. Lee Institute for Health Policy Studies and directs the Radiology Outcomes Research Lab.

“Our estimates put CT on par with other significant risk factors, such as alcohol consumption and excess body weight,” she said. “Reducing the number of scans and reducing doses per scan would save lives.”

Benefits and potential dangers

CT is both indispensable and widely used to detect tumors and diagnose many illnesses. Since 2007, the number of annual CT exams has surged by 30% in the U.S.

But CTs expose patients to ionizing radiation – a known carcinogen – and it’s long been known that the technology carries a higher risk of cancer.

To assess the public health impact of current CT use, the study estimates the total number of lifetime cancers associated with radiation exposure in relation to the number and type of CT scans performed in 2023.

“Our approach used more accurate and individualized CT dose and utilization data than prior studies, allowing us to produce more precise estimates of the number of radiation-induced cancers,” said co-author Diana Miglioretti, PhD, a breast cancer researcher and division chief of biostatistics at UC Davis. “These updated estimates suggest the excess risks – particularly among the youngest children – are higher than previously recognized.”

Researchers analyzed 93 million exams from 61.5 million patients in the U.S. The number of scans increased with age, peaking in adults between 60 to 69 years old. Children accounted for 4.2% of the scans. The researchers excluded testing in the last year of a patient’s life because it was unlikely to lead to cancer.